A wise therapist once taught me that, in times of extreme anxiety, when my body wants to hyperventilate and my brain wants to check out, I have to find a method of self-soothing. Not to ignore or argue with the anxiety, but to remind myself that it’s not going to kill me.

For most of my life, reading was the way that I soothed myself. I was able to escape into a story and ignore the noise of the outside world, and whatever I was reading would give me some needed perspective on the world outside of my own experience.

But my attention span is not what it used to be. I’ve talked to several formerly-voracious readers recently about how difficult it’s been to shut off the external noise and get lost in a book like we used to do so easily. Now, I often find myself self-soothing by turning on a TV show I’ve already seen a thousand times (Survivor re-runs are the only reason I pay for Paramount+), but more and more, I force myself to open a book and try to get lost in some part of it, even for just ten minutes or so.

Lately, most of these books are art books. It’s been astoundingly comforting to get lost in images and manifestos, especially from women who have felt as angry and scared as I do. It’s also a huge relief to give myself a break from trying to focus on reading an entire novel. A big part of self-soothing, I’ve learned, is just being willing to let yourself off the hook.

I’m including a few of my favorite works of protest art below. I hope this little snapshot offers some comfort and inspiration during what is arguably the scariest and most surreal time any of us have ever experienced.

(Note: the title of this post comes from a 2015 exhibition by Rosy Kesyer. From the press release: “Keyser’s paintings provoke the viewer to consider what constitutes beauty, empathy, profanity, and the baseness of form.”)

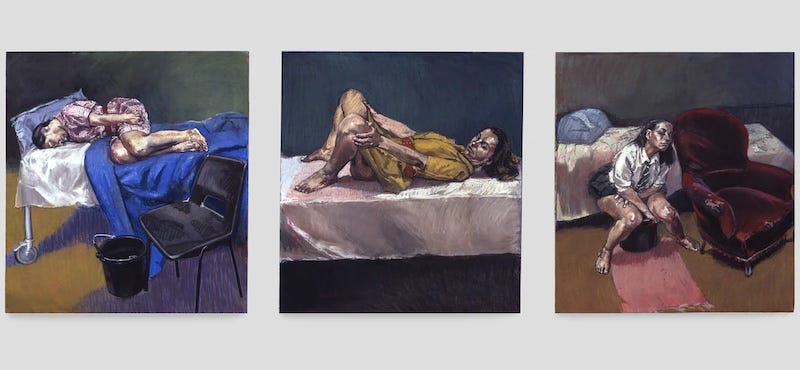

Untitled: The Abortion Pastels, by Paula Rego (1998)

In 1998, a Portuguese referendum failed—if passed, it would have legalized abortion in the country. Artist Paula Rego (b. Jan 26, 1935), whose work up to that point had already focused largely on feminist issues and abortion rights, was outraged. In the six months following the ruling, she created ten prints that depicted the dangers and realities of illegal abortions. The women depicted in the paintings are clearly in pain, and many are frightened, but none look ashamed or guilty. Each woman radiates two deeply relatable (and evergreen) emotions: determination and rage.

The works were largely circulated in Portuguese newspapers, and when a new referendum was passed in 2007—overturning the previous ruling, and legalizing abortion—her pastels were credited as a major influence.

Later in her life, Paula said: "The series was born from my indignation... It is unbelievable that women who have an abortion should be considered criminals. It reminds me of the past... I cannot abide the idea of blame in relation to this act. What each woman suffers in having to do it is enough. But all this stems from Portugal's totalitarian past, from women dressed up in aprons, baking cakes like good housewives. In democratic Portugal today there is still a subtle form of oppression... The question of abortion is part of all that violent context."

Turbulent, by Shirin Neshat (1998)

I was working at The Broad Museum in the fall of 2019, when the museum presented I Will Greet the Sun Again, a sweeping exhibition of Iranian artist Shirin Neshat’s work (b. March 26, 1957). As an exile from her home country, much of her work centers around protest, rage, women’s and immigrant’s rights, as well as what it means to have a homeland, and what it means to have faith. I was particularly moved by this video work, Turbulent, and I watched it at least once every week during the duration of the exhibition.

It’s presented as a split screen in the video I’ve included here, but in the museum, the video was presented on two separate screens in a small room by itself, with the man’s portion of the video playing on one wall, and the woman’s portion playing on the wall opposite, so that the videos (and man and woman) were essentially facing each other. This also means that the viewer has to pick a side: when you’re watching one of the screens, that means your back is facing the other one.

The man sings a classic Persian love song to a full audience, while the woman, on the opposite screen, stands silent on stage in front of an empty theater. When the man finishes his song, the woman begins to perform something that I would almost classify as sound poetry: she doesn’t sing so much as she grunts, performs breathing exercises, and creates other sounds with her mouth that sound almost feral, but also musical and strange and wonderful in their own way.

At the time of the creation of this work, and still today, women were/are banned from singing in public in Iran.

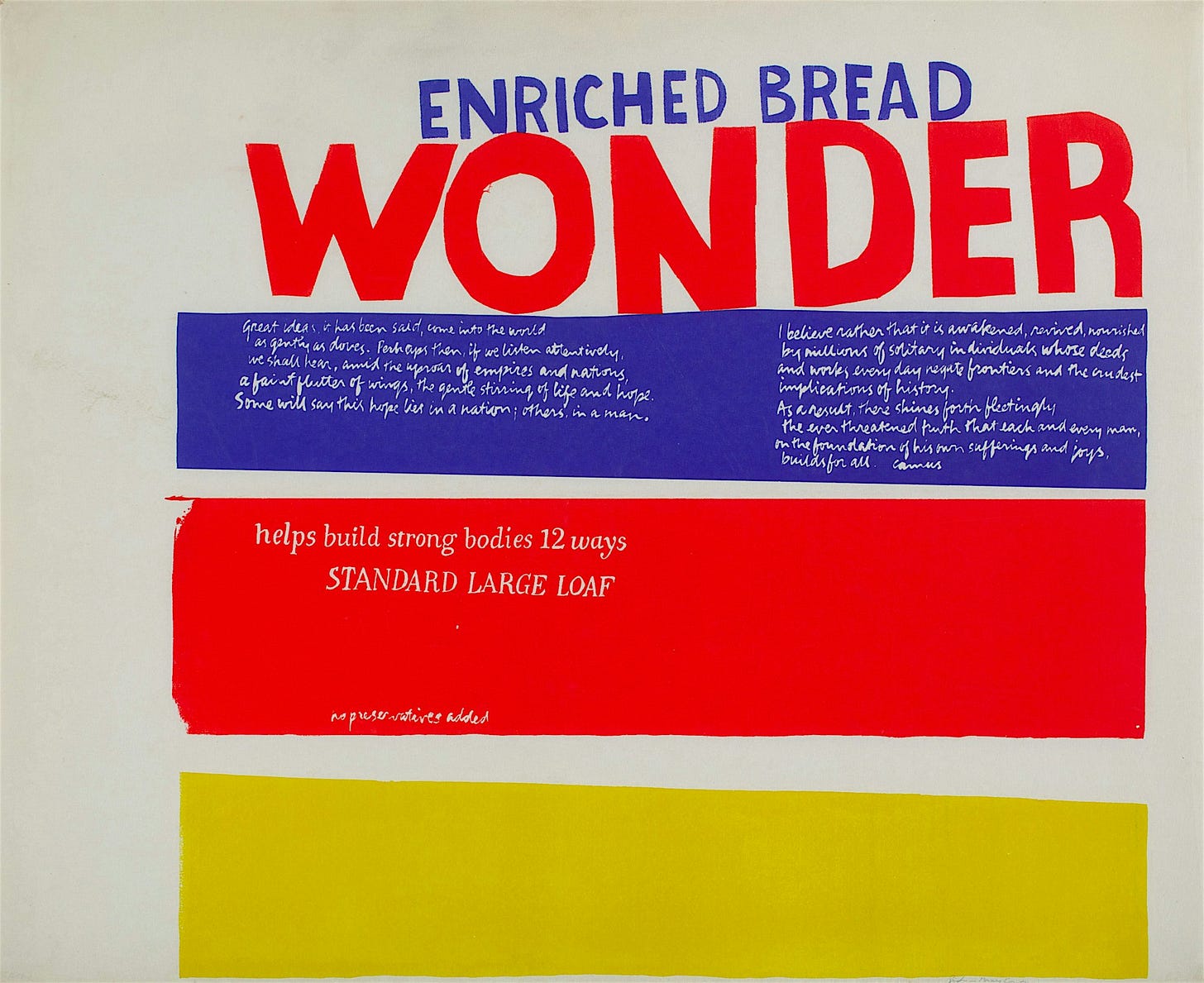

Enriched Bread, Corita Kent (1965)

It’s strange to think of a former nun becoming somewhat of an artistic revolutionary, but Sister Mary Corita Kent (b. November 20, 1918) basically did that. At age 18, she joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart (a fairly progressive order, considering) and eventually became head of the art department at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles. Many of her graphic design posters were made from collaged materials—packaging, newspaper headlines, signage—and she rearranged familiar text and logos into new messages of peace, resistance, and hope.

Her work may appear “softer” than others included here—by that I mean, less in-your-face, less graphic or brutal, less loud. But resistance is resistance, no matter how loud you turn up the volume. We need the quiet fighters as much as we need the ones on the frontlines.

Corita often quoted the philosopher, writer, and anarchist Albert Camus, as in the work pictured above. I love the idea of a former nun looking to an anarchist for inspiration. Reprinting the artwork’s text here, as it is difficult to read on a screen:

“Great ideas, it has been said, come into the world as gently as doves. Perhaps then, if we listen attentively, we shall hear, amid the uproar of empires and nations, a faint flutter of wings, the gentle stirring of life and hope. Some will say this hope lies in a nation; others in a man. I believe rather that it is awakened, received, nourished by millions of solitary individuals whose deeds and works everyday negate frontiers and the crudest implications of history. As a result, there shines forth fleetingly the ever threatened truth that each and every man, on the foundation of his own sufferings and joys, builds for all.”

-Albert Camus

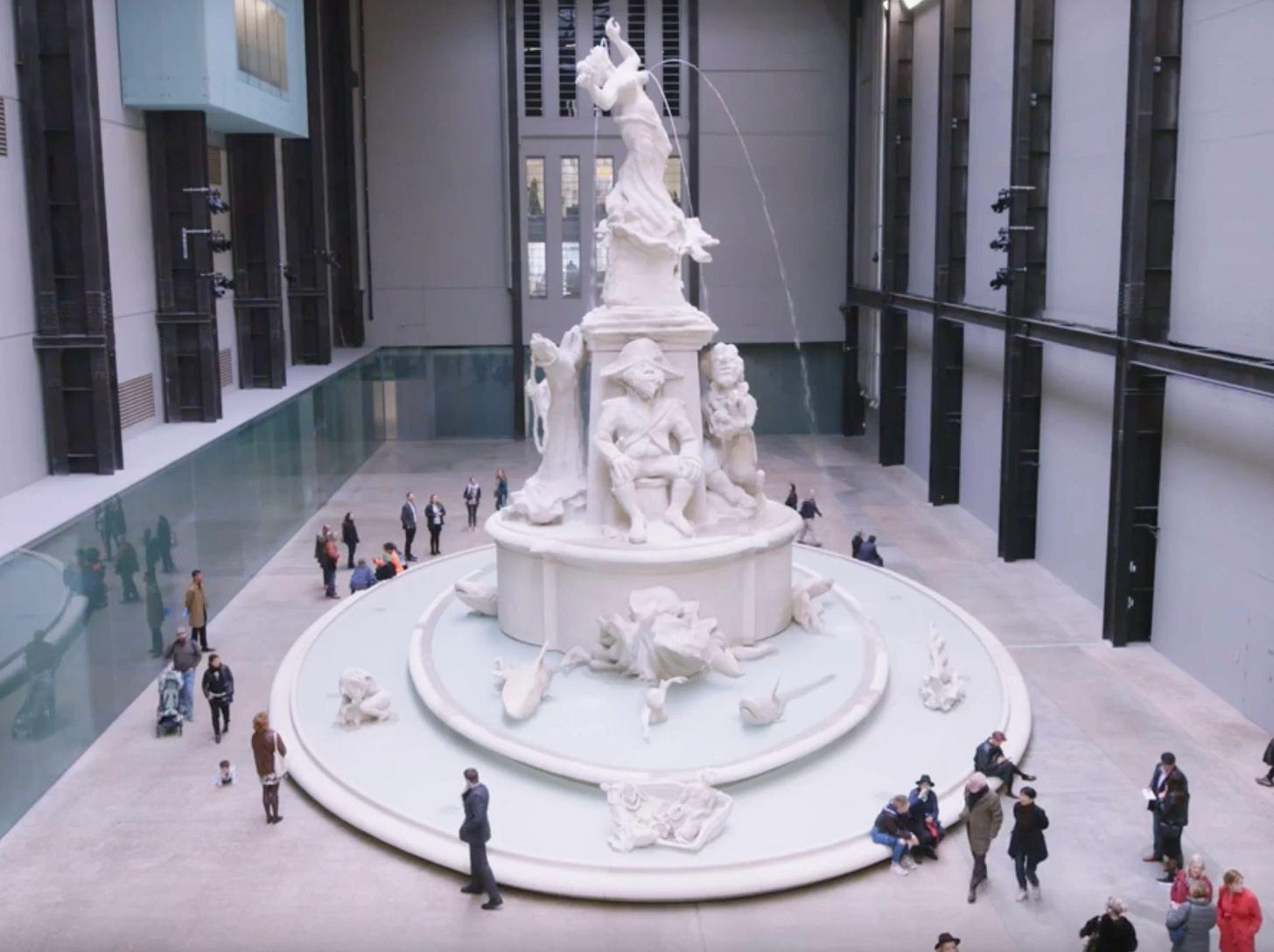

Fons Americanus, Kara Walker (2019)

I’m obsessed with the fact that Kara Walker (b. November 26, 1969) used her big Tate Museum budget to make a giant fountain that threw the ugliest parts of British/American/French colonial history back in everyone’s faces. This massive sculpture, about 40 feet tall, constructed primarily of recycled materials, and fully-functioning as a fountain, was meant to resemble the beautiful fountains and sculptures of western civilizations. But when you looked closely, you realized that the meticulously sculpted figures and narratives were all references to art history—many of them specifically referencing works by white artists who depicted the slave trade in their paintings. These brutal scenes culminated with a female figure at the top of the piece with her throat slit. Water shot out from her throat and breasts, cascading down the fountain. Haunting.

Kara was playing with the idea of monuments and statues: what do they memorialize? What do they force us to remember, and what context do they force us to remember within?

I refer to this piece in the past tense because it was deconstructed after the exhibition’s run—despite the fact that it was the most visited exhibition the Turbine Hall had ever seen in its 20 years of commissions. Pieces commissioned for the Turbine Hall in the Tate are meant to be temporary, but it would have been cool to see this one live on somewhere else in the world after its run.

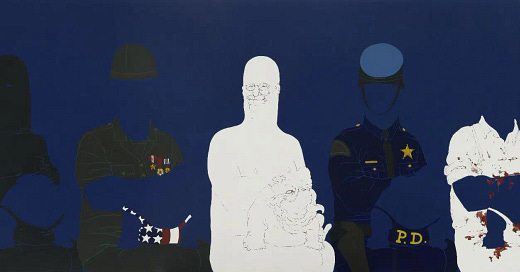

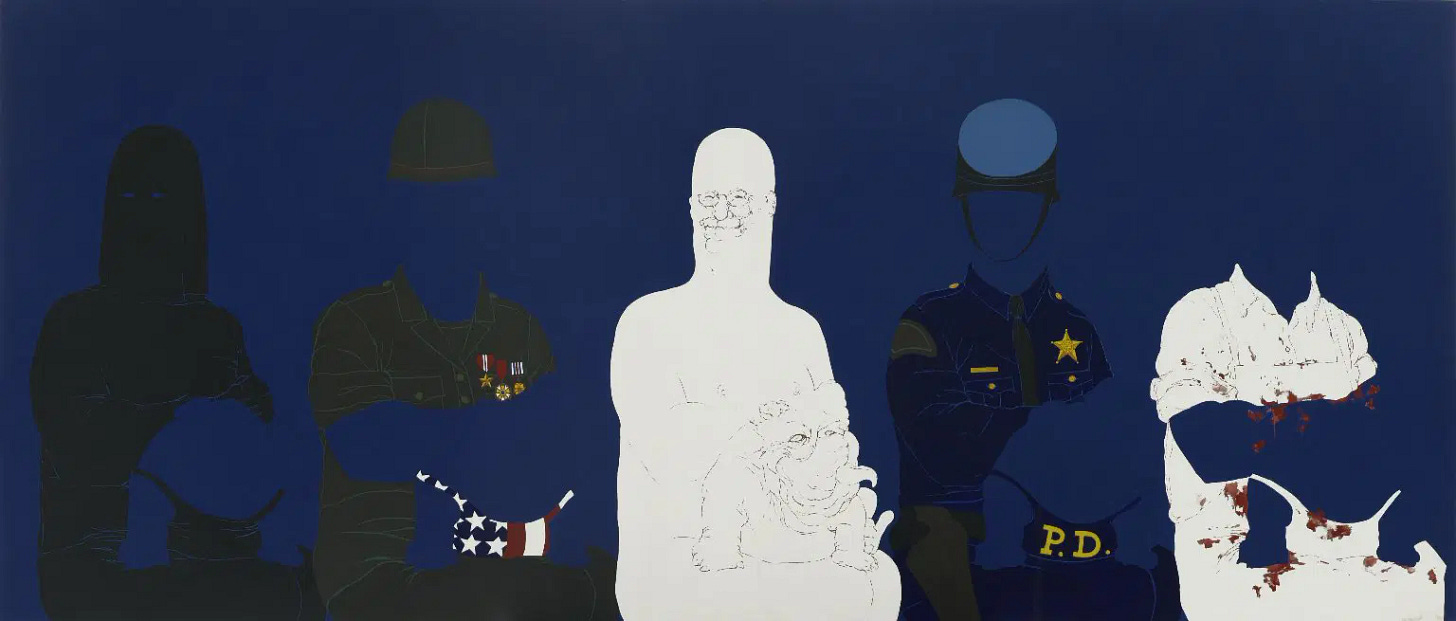

Big Daddy, May Stevens (1970)

I couldn’t talk about protest art without mentioning the Guerilla Girls. Most people are very familiar with the Guerilla Girls’ works/performances as a collective, so I want to instead focus on one of the original founding members, and her specific work: May Stevens (b. June 9, 1924). Her art and her activism were intrinscically linked throughout most, if not all, of her career. She was most passionate about feminist issues and anti-war issues. I particularly like this piece, Big Daddy, because it unsettles me every time I look at it—and because it’s one of those pieces where I notice some new detail every time I see it.

This work is held in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. Their wall text is very descriptive and efficient, so shout-out to the copywriter:

“May Stevens has been a committed political activist throughout her long career. Her Big Daddy series began in response to her disappointment and anger over the Vietnam War. For Stevens, Big Daddy takes on aspects of both the personal and the political. Based on a portrait of her resolutely patriotic father, the obviously male figure is also reminiscent of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919). Here, the figure’s bullet-shaped head exaggerates his phallic power and capacity for violence. However, by depicting him as a paper doll, to be dressed up as an executioner, decorated soldier, policeman, or butcher, Stevens ultimately strips Big Daddy of his patriarchal command.”

If you’re out protesting today: stay safe, stay hydrated, stay strong. And feel free to repeat the thing I keep telling myself: there’s more of us than them.